These paintings were exhibited at The Paris Gibson Square Museum of Art in the summer of 2021. I view the abstractions autobiographically, referencing mothering, order and lack thereof, and children’s books. Below is some text to specific works from this series.

Four Square, 2020, Four Square, 2020, Oil and PVA on panel, 36” x 96”

This work began in the mid-2000s and was finished ten years later. I first adhered large pieces of linen to each panel, which was prepared with a yellow ground. The yellow was too loud, so I covered the yellow with white gesso. I felt back at square one, so I then peeled off the linen and was surprised to find and love the large, yellow shapes left in the linen’s absence. Not knowing what to do next, I kept the four panels in my studio for a couple of years and then packed them into a U-Haul when I moved to Montana, where they sat for a decade. I hung the work on my studio wall and stared at it for weeks, not quite sure what steps to take next. I loved the huge, open shapes and was hesitant to rework it because didn’t want the surface to be too busy.

I then mixed the green and connected the color choice to my childhood bedroom, which was the exact same shade of Kelly green. Finally, I gently added thin glazes over the bright yellow forms and then finished by filling the last negative spaces with flat fields of color. When I finished, I realized that the colors I chose matched the fabric color pattern my mom used to make lamp covers, bedspread, and curtains for my room as a child. The geometric simplicity and color choice made me think of the four-square grids painted on my elementary school’s playground; the merging of memory and time.

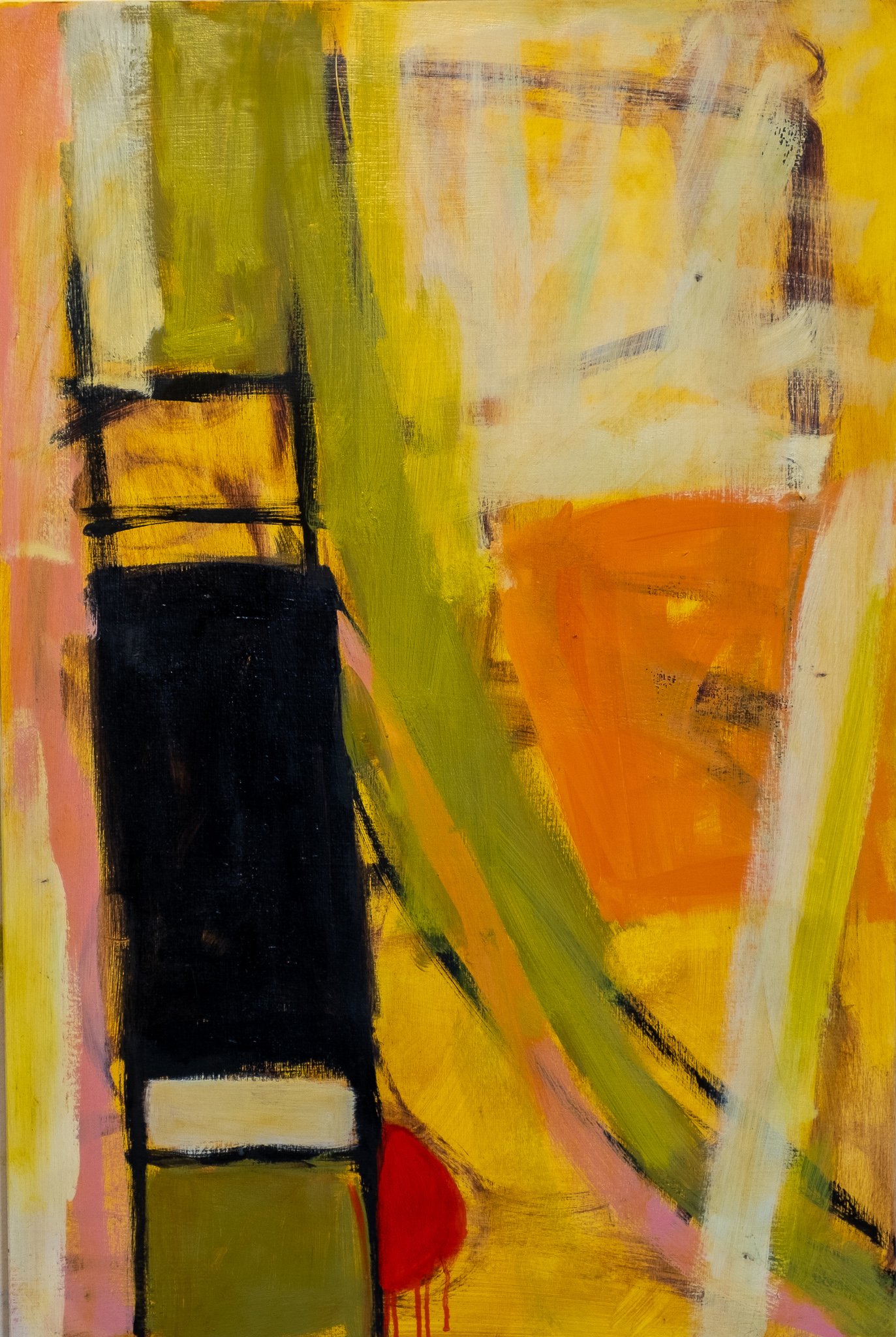

Lean In, Don’t Lean In, 2020, Oil on panel, 36” x 24”

Rather than limit myself to set dimensions, I allow myself to be inspired by other artists, or merely the collections of panels and canvases in my collection. I follow the lead of the picture plane, combined with my mood and intuition at the time.

In Lean In, Don’t Lean In, the tall panel I chose suggested that I work vertically. The upward strength of the vertical shape on the left is skewed slightly, and contrasts the right side, which gives the feeling of something vulnerable being covered or hidden by the thick green and white gestures.

The imagery leads me to think about self-censorship moments in my life—times I haven’t had the strength to “lean in” and instead hid in my silence. My silence was validated by Michelle Obama, however, who brought clarity to the complexity of power structures around socio-economic status, ability, and ethnicity of “just leaning in.” During a promotional event for her biography she said, “And it’s not always enough to lean in, because that shit doesn’t work all the time.” The gestures in this work touch on the complexity of experience as one of the marginalized. I was vindicated.

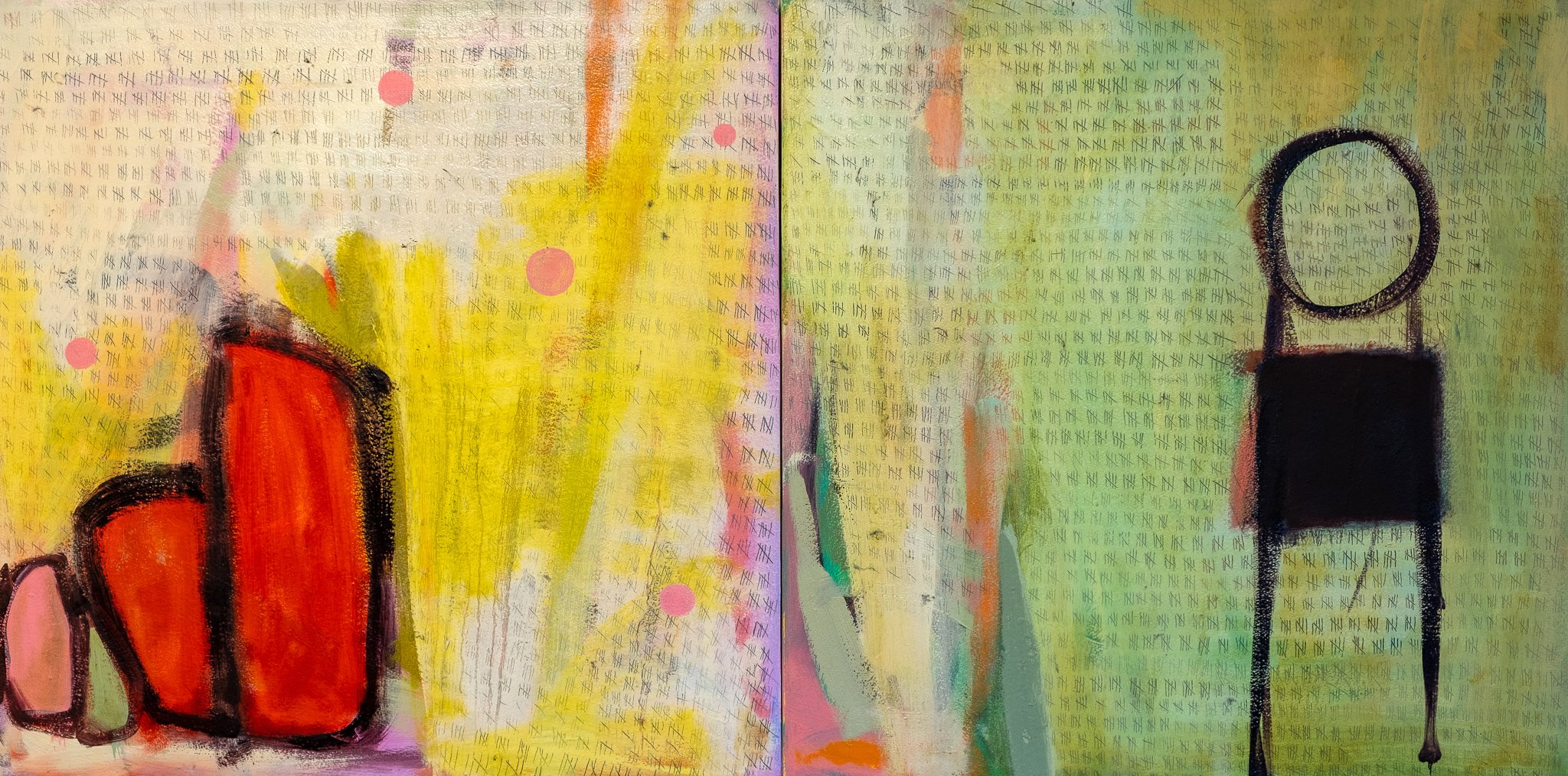

Numbers, 2020, Oil on paper on panel, 25” x 49.5”

As is the case with many white, Gen X, middle class mothers, I didn’t fully appreciate my own mom until I had children of my own. I am the third of three, born to an exhausted woman who, on top of a full-time teaching career, did far more than her share of domestic work and 100% of the mental load for our family. When I placed these two separate panels together, I immediately saw my mother in the figure on the left and the three of us kids on the right. My dad was home outside of the 9-5, but was tucked away from the chaos of domestic life, working in his office. My mom, after working all week, then worked at home.

In this painting I counted. I counted acts of labor that are visible: changing diapers, cooking meals, and cleaning. I also counted the invisible tasks of the mental load, which is the invisible emotional and managerial domestic labor post-feminist discourse has brought into the foreground. The mental load includes the thousands of invisible tasks my mother and I share. They include everything from holiday planning and shopping, scheduling appointments, researching, signing up for, and transporting children to camps, classes, lessons, etc., researching childcare and schooling options, filling out paperwork, supporting children with their homework, to communicating with schools and coaches, etc. We count and we work so the domestic structure doesn’t collapse. We mothers, instead, collapse, in time.

Story Time, 2021, Oil on panel, 30” x 43.5”

I am interested in the ways in which we construct meaning, especially in early childhood. After I chose to fill the rectangle on the right with red and white stripes, I could only see Dr. Suess’s cat in The Cat in the Hat. As an educator and advocate for young children I follow discourse on appropriate curricular materials for children closely. In Philip Nel’s study, Was the Cat In the Hat Black? he writes that the cat who rescues two children from boredom on a rainy day is a stand-in for blackface vaudeville, a statement that catapulted in mainstream culture in 2017.

I learned to read on Suess’s books. And when given a set for my own kids, I taught them to read they rhymes as well, changing wording when necessary to omit racist or sexist statements from the stories. While many of Suess’s books address fascism and support the environment, there’s the flipside, too, one that reinforces racism and stabilizes white supremacy. This work reminds me how uncovering previously unseen bias significantly changes the way in which we see an object; in this case a hat becomes a signifier of white supremacy. The left panel, with its updated palette, suggests an opening of the field of resources for children to bring new texts into the curriculum.